by Roger Pe

Philippine Daily Inquirer

Advertising is a double-edged sword. It can cut down your competition to size or it could backfire.

It could be your best ammunition for generating sales or call attention to your product flaws.

It could make your product very desirable. It could expose your brand to closer scrutiny against competition—benefit for benefit, feature for feature, strength for strength.

Many brands have reached iconic levels because they gallantly stood the tests of time and evolved with the changing needs of the world.

Look at Apple. It rolls with the times and Steve Jobs, before he died, kept saying, “Stay hungry. Stay foolish.”

20 years and counting, and not just existing—but continuously improving to keep people’s lives a little better. That’s what brands should be.

When brands improve with the times the results are beautiful. Harvests are aplenty. They bust sales charts and laugh all the way to the bank. Does your favorite brand belong to this category?

“Quite a number of brands are now better off forgotten because they made more harm than good to consumers,” says a marketing guru.

Some brands, like detergents and deodorants, were harmful to the skin consumers just stopped buying them. They caused not only allergies and skin rashes they also left stains and darkened some sensitive parts of the body like armpits.

They contained harsh formulations, aggravating frustrations of people who used them.

A number of consumers have also become allergic to some whitening soap and cream brands for causing facial blemishes and rashes.

Many, for sure, will have horror stories to tell about brands that make promises they don’t deliver—soaps that melt easily and last only a couple of days; detergent powders and bars that don’t give much cleaning power and lather.

Acne ointments that only made your zits worse, anti-perspirants that do the opposite, moisturizers that make you look greasy all day.

Scents that dissipate in a few minutes after wearing them.

Hotel and restaurant bills that are not worth the hard money you pay for.

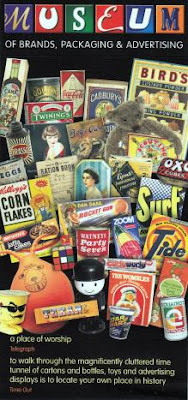

These brands are best forgotten. They would never be archived in London’s Museum of Brands, the largest repository of existing brands and those that died through the years.

Museum of Brands, as the name implies, houses an astonishing collection of brands collected by social historian Robert Opie. It is a “‘trip down memory lane,” according to its website, beginning with the Victorian era down to the present day.

As one steps into the premises, visitors will be overwhelmed by the amount of items on display.

Every inch is filled with packages, toys, games, books and ads from each era of the bygone days.

Great brands, bad brands

“There are great brands and brands that are just brands. There’s a big gap between the two,” says a veteran ad man.

“Some brands were ideas created with consumers in mind. Some brands were made just to get fast bucks out of naïve consumers,” he says.

“Oh, yes, some brands belonged to the flash-in-the-pan category,” he laments.

The black panty liners

“The color black rocks,” says a famous panty liner brand on its blog. “It does the job when it comes to feminine hygiene and 66 percent of women say it’s a favorite because it’s comfortable, breathable, dermatologically tested, unscented and discreet.”

Ten years ago, another packaged goods multinational giant launched an all-black version of its top feminine hygiene product.

In order to create excitement in Europe, it launched a web auction of used black clothing’s donated by celebrities. Imagine owning a piece of black dress from Mel C of the Spice Girls, and American actresses Brooke Shields and Meryl Streep?

Throughout the promotion, the auction site logged in 45,000 visits and averaged 5,000 daily hits. All proceeds from the sale went to charity, and the company was hoping the goodwill generated would rub off on its panty black liner products sold in some countries in Europe.

What happened?

Consumer acceptance, among the ladies of course, was lukewarm.

The packaging was great. And because it was thin and small, it was easy to slip in a small purse and women can be fresh all day.

The product had an odor control, which kept women smelling fresh at the end of the day. The only problem women found out was that the adhesive left marks on the underwear, a negative attribute many women disliked.

The product was launched in Manila in 2002 by J & J Philippines in an all-black party in Makati.

A check with the distribution network of black panty liners in the Philippines, specifically big Makati supermarkets, reveals that they are not available anymore. They can, however, be purchased online.

Starts with the product

Many great men in advertising always referred back to the product as a marketer’s best weapon for advertising. “No amount of advertising can sell a bad product. It will only enhance its demise,” says Bernbach, the famous B in the DDB acronym.

Another advertising icon, Leo Burnett, gave us two of the most often quoted lines about a product: “The greatest thing to be achieved in advertising, in my opinion, is believability, and nothing is more believable than the product itself.”

“We want consumers to say, “That’s a hell of a product” instead of, “That’s a hell of an ad,” Burnett said.

Another advertising great, David Ogilvy, stated: “It has taken more than a hundred scientists two years to find out how to make the product in question. I have been given 30 days to create its personality and plan its launching. If I do my job well, I shall contribute as much as the hundred scientists.”

A product that delivers and keeps abreast with the times has a bright future of making it a brand. Great products make great brands.

And a great brand will forever remain in the hearts and minds of consumers. Bad brands will pass like a ship in the night, virtually not remembered and buried in the dustbin.

Complete stories on our Digital Edition newsstand for tablets, netbooks and mobile phones; 14-issue free trial. About to step out? Get breaking alerts on your mobile.phone. Text ON INQ BREAKING to 4467, for Globe, Smart and Sun subscribers in the Philippines.